Port Robe and Shipwrecks

The following material relating to seven of the most significant shipwrecks on the Limestone Coast and activity in the Port of Robe is taken from the writings of Henry Dudley Melville, who served as Harbour Master, Sub Collector of Customs and Receiver of Wrecks, based at Robe, from 1855 to 1869. Disillusioned by his treatment as a public servant over a career spanning almost 40 years, he wrote pointed memoirs in the hope they would convince the government to pay him compensation. There are some discrepancies in his account, which may also be attributable to the fact it was written in the late 1880s, many years after the events occurred.

A full transcription of Melville's Compensation for A Life’s Service under Civil Service Regulations of South Australia 1887 is available to read online, in five parts, via the State Library of South Australia website.

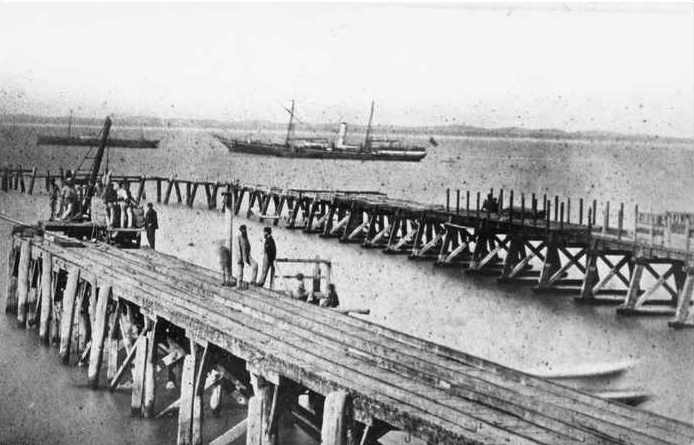

Image: Port of Robe, 1870

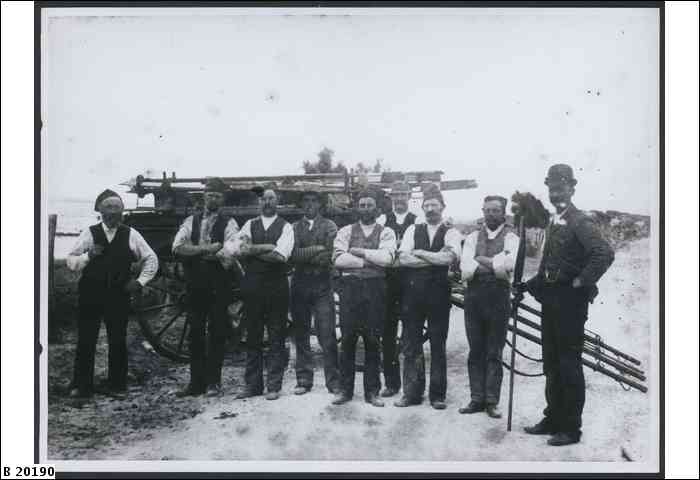

Image: Robe Lifeboat Crew, 1887

Invasion of Chinese to Robe 1857-1858

The Chinese Invasion in 1857 and 1858, the Victorian Government had imposed a poll tax on all Chinese landing in that Colony of ten pounds per head and a heavy duty on opium. South Australia allowed the Chinese to land free, and charged only five percent ad.val duty on their opium, so the Mongolian landed with his opium in South Australia and walked across the border to the Victorian gold-fields. Some forty-five vessels varying in tonnage from five hundred tons to two thousand tons, came direct from Hong Kong to Port Robe, landing about twenty thousand celestials inclusive[1]. Many hundred landed by the inter-colonial steamers from Adelaide as each Chinaman paid his boat hire and cost of drays, guides etc. This influx must have put in circulation at Robe not much less than twenty thousand pounds stirling in gold and silver.

The Robe people were not prepared for this sudden invasion, and neither was I. The thing had been kept very quiet by Hong Kong agents in that the Victorian Government might not interfere with their wholesale smuggling. I had to get a pilot appointed, and engaged side-waiters to stop smuggling. I had often to call in the aid of the Police. At one time there was no less than three thousand pig-tails camped in and about Robetown, on one occasion they broke open a store in which I had secured their opium until duty was paid. I was then obliged to call the attention of the government to the state of affairs, and a detachment of the 12th Regiment under Lieutenant Saunders, was sent down. Robe became exceedingly lively now - too much so for me. My resources were not at all equal to the occasion, but as it was only a temporary demand, I had to make the best of it.

Many splendid American liners arrived. The "Young America" brought a thousand Chinese passengers, she was a two thousand ton ship. The "Challenger", the "Queen of the Seas", the "Phaeton", and other large vessels were employed in the trade. The Masters of course were anxious to get cleared as soon as possible, many of them not being prepared to ride out a gale, their chains never having been out of the locker and in some cases vessels had not sufficient length of cable. It required one hundred and twenty fathoms to ride out a gale with security. I often worked night and day to get those ships out of harbour and was as pleased to see their foretop sails in the offing as the Captains themselves. Those were the gay times for the little Town of Robe - plenty of money and plenty of fun.

A German brass band took up their quarters in Robe for some weeks and did several Balls every week and the servant girls were in great requisition. Those who could not dance learnt. We had a very nice girl at the time but she went nearly off her head what with the fascination of a good looking fellow in the band. And the dancing, poor Annie had but little time or thought for her domestic duties. I remember one day going into the kitchen to see if there was any chance of getting tea when I found Annie dressed up engaged in practicing the polka one two three four.

The boatmen charged the Chinese most exhorbiting prices for landing, varying from five to ten shillings per head and many made enough money to buy a boat so that one had quite a flotilla of fine boats. The action of the boatmen often led to disturbances and the Chinese knives were unsheathed but no serious affray took place. Many of the passengers were half-bred Malays and very fond of showing their knives.

One night when landing was going on I took a small box of opium from one fellow when he drew his knife and not caring to incur the risk of getting it between my ribs I planted a blow under his ear that knocked him off the jetty. He fell between a lighter and the piles. Fortunately for him and me too the boatmen dragged him into the lighter before any further damage was done. I had a rare chance of making money at this time but as an Officer of Customs was under a heavy bond not to in any way engage in trade, so had to be content with my twenty pounds a month and an occasional guinea as overtime.

Receiver of Wrecks

The most painful duties I was required to perform while on this port of the coast were in connection with wrecks and of this I had a great deal. The wholesale destruction of property is a painful sight, but where you are compelled to witness the lives of your fellowmen destroyed your occupation becomes distressing. I will give a brief sketch of each of several wrecks that in my capacity as receiver, I was bound to look after.

Wreck of the Phaeton - 2 February 1857

This was the first wreck I had at Port Robe. She was a splendid ship of a thousand tons and quite new. She entered the harbour on 2nd of February 1857. It was a beautiful morning, a light breeze off the land. The Master would not heave to for the pilot but sailed up the bay in grand style but went too far before putting his ship about. When he did she missed stays and drifted on to a sand bank from which she never came off. No lives were lost but the vessel became a total wreck. The greater part of the between cargo was saved - tea, opium, silks and chowchow, a large quantity of linseed oil was also recovered from the lower hold undamaged. I think I collected over 300 pounds custom duties on cargo saved. This wreck damaged the character of the Port but was entirely owing to the fact that the Master did not make use of the service of a pilot when they offered.[2]

Wreck of the Sultana - 27 April 1857

This was another wreck arising from the sheer recklessness of the Master. Had he waited for the pilot his vessel would not have been lost at Port Robe but instead of doing so he took the vessel over the reef off Cape Lannes and struck so heavily that the vessel sprang a leak and (as he stated) for fear she might sink in deep water he ran her ashore on the rocks.

There was something about this wreck and Master that I could never get cleared up. The real master of the ship had died at sea and the man who lost her was the Mate. I received some pitiful letters from the poor widow of the Captain, the owner refusing to pay her husband's salary until they received a statement from his successor which I doubt if they ever did. I heard many months after the wreck of the fellow being in Melbourne carrying on top ropes to use the nautical phrase. At Robe he declared he had no money.[3]

Wreck of Agnes at Cape Jaffa - 13 March 1865

I received information of this wreck from the only survivor who got ashore on a raft. I remember his name he reported that he had left the Captain alone on the wreck some three days previously and the he thought we might save him, so no time was to be lost as time was the great object. I decided not to take the life boat (which produced a howl from the newspaper correspondent) but took the Coxswain Fullarton and one of the I. Noble. We left Robe about 4pm hoping to reach scene of wreck that night. I also took the survivor to point out the position in which he left the wreck. We kept under sail, rather too late to secure a safe anchorage and got amongst some broken water and in some heavy seas came rolling in during the night we feared much our chain would part in such case the Robe people would have had to search for our bodies. I know it made me think of my wife, children and Insurance Office, as I've said before my coxswain Fullarton was a fine fellow and never lost his head. So by keeping a close watch and a stout line on our chain we rode out the night and when day broke made sail for the Margaret Brock reef. For a long time we could see nothing of the wreck, but at last finding some floating spars and rigging we concluded that the schooner had broken up and we should find the Captain lashed to some portion of the stern, so beating on and offshore we discovered about midday a part of the wreck and a signal lashed to it and made at once for the spot. As we neared the object I could with a powerful glass see a body on the star board quarter of the wreck, and our spirits rose immensely. He's asleep thought one, worn out with exhaustion thought another, surely he's not dead we all exclaimed and sincerely hoped but alas he was dead as a doornail. What killed the poor fellow, I could never understand unless finding himself drifting away to sea he gave up all hope and died broken hearted. When we found his body garments and the sailor told us he had some biscuits and water when he left him four days previously.

His name was Taylor, his brother was keeper of the Queenscliff Lighthouse at the time. I took his body to Lacepede Bay and held a post mortem for examination and inquest. He was then buried in the Kingston cemetery but his relatives expressing a wish to have the body buried in Victoria, George Omerod with his usual kindness had the body taken up and placed in a special constructed coffin for shipment to Melbourne and a tombstone and railing now mark the spot.

I received a very nice letter from Captain Taylor's relatives but not a word of approval from the head of my department, although myself, the coxswain and the boat man had risked our lives in the attempt to save our fellowman. As Harbour Master I was bound to submit but felt it more on the main account for there was not a smarter set of men on the coast than the crew of the Port Robe life boat, all used to pulling together in discharging and loading vessels, nearly all in the employ of Mr. George Omerod. He never kept a useless man considering the nature of the service a life boats crew should receive every encouragement.[4]

Wrecks of Alma and Livingstone - 15 & 16 December 1861

These two fine vessels were driven ashore in Guichen bay during a hurricane that swept the coast and did immense damage. Barring cyclones in the tropics it was the fiercest storm I was ever in. It was from the North-West and out of the sea. The "Livingstone" was a fine ship of about 600 tons loaded with wool and ready for sea riding at the usual anchorage with her ordinary anchor and chain.

The "Alma" not so large or a fine a vessel was in ballast and not much of that as she was discharging it at the time and was away from the usual anchorage in seven fathoms of water and exposed to the full force of the seas and the wind. She had good ground tackle but the strain on her chain was too much to stand long. I had the lifeboat on its carriage with a fine crew ready to launch should the signal of distress be given. The men on board knew that our lifeboat could not take men off the vessel and land them without great risk of all hands being lost. No number of men could have pulled that lifeboat back to the landing against so fierce a hurricane and had the attempt been made for a certainty the boat would have been driven ashore among the breakers.

The crew were safe on board while her anchor held and they knew it, the only assistance we could have rendered would have been to take off coir springs to ease the chains but we had no such warp which was a decided want.

A newspaper correspondent at Robe cajoled me a good deal with his opinions, "what's the use of lifeboat it you don't use it? If that vessel goes ashore in the breakers all hands will be lost. Mr. Melville you are running great risks to all," which I could only respond with "Mind your own business." No signal of distress has been hoisted, the crew are safer where they are. It was a trying time but I had a splendid fellow as Coxswain of the lifeboat in whom I had every confidence and his opinion would have swayed me about midday. The "Alma" parted from her anchor and the mate (Swan) ran her ashore in a little inlet of the rocks under a cliff. Now was the time for the lifeboat crew to act and so we did to some purpose, all hands with the rocket apparatus were speedily on the cliff. Out first rocket line driven by the gale over the stern of the ship her masts were all cut away. I lowered the elevation of the next rocket which was a mistake as the rocket line had become heavier with saltwater so the line fell short. While preparing for a third trial the Captain (who was ashore when the gale set in) gave it as his opinion that the crew would not leave the ship if we did get communication. He said they would never be such fools as to risk their lives on the warp, they were safe enough where they were. This from an authority made me hesitate and reflect. Coxswain, what do you think? Oh, she may remain jammed in the rocks or she may not. The conclusion I came to was this - that while I had a rocket left (I had only one) it was my duty to try and get communication with the ship. If the men would not run the risk of coming on the warp the fault would not be mine. The sequel will show that I was right in taking the action I did. With the third rocket we got our line over the ship, and now another and unforeseen difficulty arose with a wreck it is necessary to establish a circle by means of an endless line working the cradle buoy on the warp - and this the buoy is worked to and fro. This we had done but those on board not knowing the working of the apparatus let go one end of our line. Here was a pretty go, now what was to be done.

There was only one thing to do, and that was some one of us to get on board and explain use of the tackle and start the first man, but who was to do it. Several volunteered, at last it was generally agreed that the coxswain should undertake the service, no man better able but he was a very tall and heavy and therefore incurred a greater risk than a lighter man. However he succeeded. We got him safe on to the wreck but on returning the warp dipped just over a boulder and he received a nasty blow on the back from which he suffered for a long time. The gear was in good order worked well and one by one we took off 24 men, but it was only by the greatest care. The vessel surged heavily and strained the warp to the utmost tension before we could slacken. We had to haul in slack and pay out again every few minutes or the warp would have parted and we would have lost the man on it and all that remained on the wreck. It was indeed a most anxious time - had any of the men been lost yet the vessel held together as the Captain predicted. I should have been severely censured, and this I felt and what was worse that instead of saving I had helped a fellowman out of this world. Alls well that ends well, and nothing succeed like success and we succeeded.

All this time the "Livingstone" was riding out the gale gallantly and we thought her safe, she was less exposed than the "Alma". I had set the watch and gone home to lay down at about 1am on the 16th but was soon aroused again by the watch with the unpleasant information that the Livingstone was drifting. She had parted from her best anchor and was now dragging two lighter ones. She took the ground about daylight but as the gale was abating we had no fear of her breaking up. The boat was now manned and all aboard were taken off.

When day broke there was nothing to be seen of the Alma but her nose and only a few feet of that. She had been lifted nearer the shore and smashed into thousands of pieces and scattered over ten miles of beach. I can't say that we saved the crew of the "Livingston". They might have got off without our aid, but this I can say that but for the rocket apparatus and the crew of the Port Robe lifeboat not a man on board the "Alma" would have been saved. They would all have been dashed to pieces on the rocks, and this the crew knew and acknowledged. What the Captain thought I don't know I didn't ask him. I had every reason to be thankful that I had adhered to my determination to try and get communication with the vessel when I had a rocket left. The assistance gave the Life boat crew a dinner at which we received the thanks of those saved, but no recognition of our service was made by the Authority that should have been done so. My Chief never cared to give prominence to any maritime action of his officers where his own cocked hat was not seen. The Coxswain Fergus Fullarton should have received a medal. He was a fine fellow and risked his life on that occasion. I did all that an officer in my position could do, in directing attention to the matter without wanting self-praise.

As receiver of Wrecks I obtained the aid of Mr. Omerod & Co. of Robe and by their men and boats the cargo of the Livingstone (wool) was taken out and realised nearly its full value, forty thousand pounds, but for the aid of George Omerod Esq. the Insurance officers would have lost this amount. Although I received no acknowledgement from the head of my Department I received a letter of thanks from underwriters and fifty pounds.[5]

Wreck of the SS Admella - 6 August 1859

These are painful recollections to call up, and none as much so as the loss of the Admella S.S. I have always held and still do, the opinion that the loss of the fine Steamer and the many lives was mainly attributed to the desire...

She broke her back on the reef - canting over, those saved were lashed in riggings, the great loss of life was when the vessel parted. I believe some 80 lives were lost altogether but writing from memory I can't give exact number. I know that only 22 were saved, 19 by the Portland lifeboat and 3 by our shore boat, one of the number being the Captain. The vessel struck the reef on the night of the 6th August and the rescued were on the wreck 8 days. I was in charge of the shore party under the Trinity House and a fearfully harassing time we had of it. All Adelaide was in a state of great excitement and messengers were kept continually going between Mount Gambier and the scene of the wreck bearing messages of the most extra-ordinary characters. Some suggested catamarans of a means of getting at the wreck, and one begged that I would not lose sight of the fact that oil thrown on troubled waters had proved a success - the troubled waters we had to contend with was the heavy seas breaking on two lines of reef between us and the wreck. The only opening was from the seaside, and the first attempt of the life boat to approach the wreck from the sea failed. The people of Adelaide could not understand why day after day no plan was devised to get communication with the wrecked vessel. Upon my visit to Adelaide shortly after the wreck I showed the Governor Sir Richard McDonnell a sketch I had made which fully proved the impossibility of our getting at the wreck from the shore until the seas went down. I now give the sketch then made. Better men or stouter hearts could not be found than many of the sailors and boatmen that waited on that shore night and day for a week hoping the seas would go down and we should be able to launch our boats, one a whale boat and the other a boat from the wreck that had been patched up. Neither of them would live in broken waters. Driven to desperation B Germein and a volunteer crew did make one attempt and nearly lost their lives. The boat was capsized like a nut shell in the first breakers. One poor fellow had his leg terribly lacerated. I had to be careful that no man entered the boat except as a volunteer. To have made another attempt would have been madness. To keep alive hope amongst the sufferers we kept large fires alight in the sand hills all night. "No vessel could have mistaken three bush fires from Cape Northumberland Light when that light on view on the morning of the day the survivors were taken off the wreck, 14th August 1859. The sea at day break was calmer than at any time since the wreck and as the "Lady Bird" Steamer was not in sight with her lifeboat we decided to launch our shore boats. It being arranged that if the lifeboat was in sight I should signal shore boats to return, which I did but not before Germein had got his boat alongside and the Captain and three passengers into it. The other boat could not get over the second reef and was returning, we landed three out of the four from the wreck. One was lost in landing. He was a pedlar and quite mad.

The life boat succeeded in getting off the remainder (one a girl Ludwick) and putting them on board the Ladybird Steamer. They were at once taken to Portland Bay and I believe all recovered. We rigged a Gypsy Tent for our three who were attended by Dr. Whell. Their feet were like enormous black puddings with indentations where their toes were. The Captain suffered in mind as well as body. We watched them all night and kept their feet well attended to. I had not slept for three nights. Now that the excitement was over we knew the worst reaction had set in and I could have slept for a week. I was awoke by Inspector GB Scott to relieve him and take morning watch over our saved ones. After giving them their medicine and anointing their feet I sat at the mouth of the tent with an arm around the pole and tried to keep awake when I was most thoroughly awakened by the shrieks of the Captain whose mind was at work in his delirium. He was reviewing the whole scene of the wreck on that terrible night she struck, "Oh! the poor women and the children. Oh! My God save them, look look!" My hair was on end. I wanted to sleep no more. Poor fellow - remorse had something to do with his ravings. I give the incident most worthy of note in connection with the wreck of the "Admella". No bodies were washed ashore the only body recovered was found at Cape (?) a long way south of the wreck. The first attempt to get ashore was made by the Mate. He was seen by those on the wreck till near the shore when it was supposed he became exhausted, or not being able to free himself from the life buoy he had secured to his body he was taken out to sea. Strange to say two horses got ashore without injury. One a racehorse (Bachor?) and another a grey draught stallion. We found the carcass of one fine old racer (Jupiter) and gave it a decent burial. Many old Colonists will remember what a splendid horse Jupiter was. I give a copy of a lithograph of the Trinity House of this proud old horse.

The first report of the wreck was made by two sailors Leach and Knapman who were lucky and plucky enough to get ashore on a raft and walked 20 miles along the coast to the Cape Northumberland lighthouse. I think it was the second day after the wreck. There were many touching incidents that I cannot remember but may be found recorded in a little pamphlet published at the time.

There is always one painful experience in connection with wrecks and that is the presence of those who go for no other purpose than plunder and we had a number of those bipeds to deal with. My old friend GB Scott was then Inspector of Police and had several of his men on the beach to protect property. One of the passengers of the "Admella" was known to have some 700 sovereigns on his person and his body was hopefully looked for by the wrecks but never found.

After the wreck I had to get the pilot boat and crew to Adelaide overland to Port Robe and from thence by steamer. It was rough work for the poor fellows but better than risking their lives in an attempt to reach a vessel in the boat with heavy breakers to cross.[6]

Wreck of the Koning Willem II - June 1857

This was a large Dutch ship. She parted from her anchor and went ashore on the long beach during a heavy gale from the north west. She had landed her Chinese passengers and was ready for sea when the gale set in. She had only sixty fathoms of chain on her best anchor and being in ballast only, was very light, so that she offered great resistance to the gale. Her chain cut clean though to the windlass and passed out of the hawse pipe before it could be secured. She was not many hours on the beach before she became a complete wreck. As soon as the vessel stranded, the townspeople flocked to the scene to render assistance in landing the crew through the surf, the break being very heavy. At my request Lieutenant Saunders of the 12th Regiment and a detachment of his men went to the beach to secure and guard everything washed ashore. At this time there was no lifeboat at Port Robe, but a smart boat crew in the employ of Messrs Omerod & Co. were on the spot and carried out a way into the surf as far as possible hoping to catch a line from the wreck and thus establishing connection with the shore and by this means land the men through the surf. Before this could be done the wrecked sailors had their launch alongside and crowded into it, the Captain being the last man was ready to leave the wreck when one of is sailors cut the painter to save the launch from swamping. The boat being free drifted from the lee of the ship and before the men could ship their oars and put her stern on to the seas the boat being broadside on capsized and those who could not swim were clinging to and drowning. Those who could some were carried out to sea by the draw back and lost and but for the warp we had tailed onto, all would have been lost.

I have no record of the numbers but I think we saved 15 and about 10 were lost. The Captain who had been left on the wreck got off along our warp about 10 o'clock at night. It was a horrible sight to see the poor fellow drowning a few yards only from safety. Being a strong man and a good swimmer I was able to render good service. The danger we had to contend with was being struck and disabled by the floating wreckage. We were trying to reach one poor fellow who was holding on hard but the draw back carried him out of our reach amongst a lot of rigging and we saw no more of him. He was probably stunned and carried out to sea. This was my first attempt at swimming in surf, and I learnt this lesson, not to trust to my power as a swimmer, but go with the seas and when they break get under and cling to the bottom. Attempt to breast the drawback and you're a gone man. Some of the laddies were recovered next day (I think five) and buried in the sandhills. It was difficult to say how many bodies for dog fish has made such havoc amongst them. I remember seeing dog fish hanging on to part of a body until a trooper (who was trying to land) had got it nearly ashore. The trooper, a smart young fellow (J. Ewins) had some rough and dangerous work in recovering the bodies. If this vessel had 120 fathoms of chain to her anchor as she should have had she would have ridden out the gale. The holding ground in the bay could not be better, the ship like many others that come into port had never been at anchor in an open roadstead and was not properly found for such work. Her chains had never been out of the lockers and thus more discredit was thrown on Port Robe by its opponents.[7]

(These excerpts from Melville's writings were provided by the Robe Branch of the National Trust of SA.}

[1] Official figures gathered from customs and newspaper reports indicate the figure was more likely around 16,500. A total of 14,675 landed at Robe in 1857, and another 766 in 1862 and 1863. No consolidated records are available of the number of arrivals via coastal vessels in 1856.

[2] An American built clipper on only her second voyage, the Phaeton was carrying 260 Chinese passengers picked up in Hong Kong. It took several hours for police troopers and boat crew to rescue them, with some of the passengers being washed off a raft before eventually making it to shore.

[3] The Sultana was also carrying passengers from China when she struck the reef off what is now known as Cape Dombey. No lives were lost. The vessel and her salvaged cargo were sold at auction a few weeks later, with the list of items up for sale including 80 tons of rice, 15 baskets of ginger and 20 packets of Chinese medicine.

[4] The Agnes was bound for Melbourne with a cargo of wheat from Yankalilla when she was wrecked on the Margaret Brock Reef at Cape Jaffa. All but one of the six crew died. The lifeboat coxswain Melville refers to is Fergus Fullarton, who received a medal for bravery for his attempts to help rescue survivors of the Admella shipwreck at Carpenter Rocks in 1859. Highly regarded by his peers, he was voted to be coxswain of Robe's first official lifeboat crew when it was formed in 1861.

[5] Miraculously, no lives were lost from either wreck. Wool salvaged from the Livingstone fetched about £40,000 when it was sold at auction several weeks later, attracting interest from buyers in Melbourne, Sydney, Portland and Adelaide.

[6] The wreck of Admella remains the greatest loss of life from a single incident in South Australian history. Of the 26 crew and 87 known passengers, including many women and children, only 24 survived. None of the children and only one woman, Bridget Ledwith, survived the terrible ordeal.

[7] Sixteen crew members died as a result of this wreck. The ship had arrived in Robe five days earlier carrying 397 Chinese from Hong Kong. They suffered a terrible journey because of the state of the ship, working day and night at the pumps to keep her afloat.